The display of the show:

Views of „Michael Grossert. 3 Playgrounds 1967-1975“ at New Jerseyy with single polyester elements of the climbing sculpture/playground for the settlement on Moosjurtenstrasse in Muttenz, Switzerland, 1971. Image New Jerseyy

View of the model for a play landscape of polychrome concrete for the Résidence Grétillat in Vitry-sur-Seine, France, 1974 (not realised). In the background: two images of Michael Grossert’s Playground for Aumatten Primary School, 1967/restaured 2009, in Reinach, Switzerland. Image New Jerseyy

Views of „Michael Grossert. 3 Playgrounds 1967-1975“ at New Jerseyy with a plaster model of the Playground for Aumatten Primary School, 1967, in Reinach, Switzerland. Image New Jerseyy

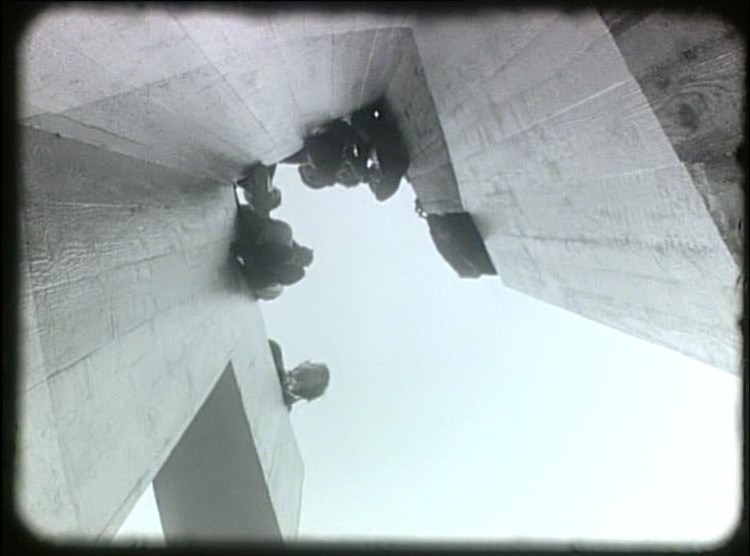

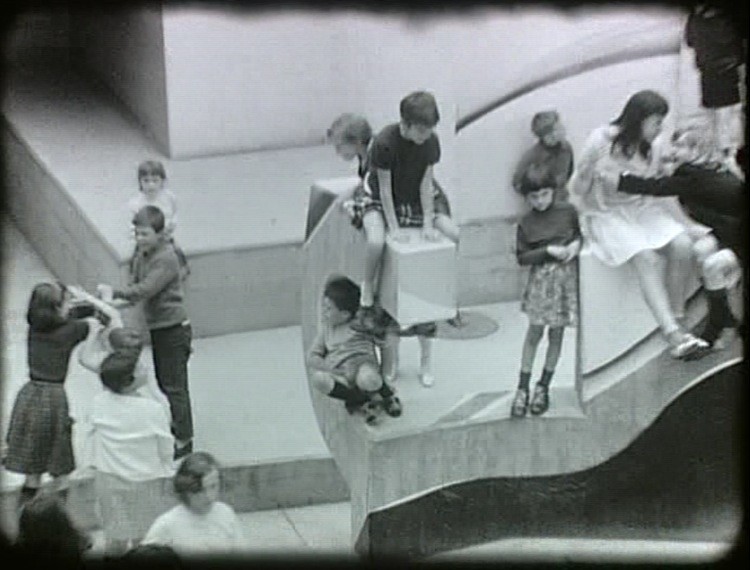

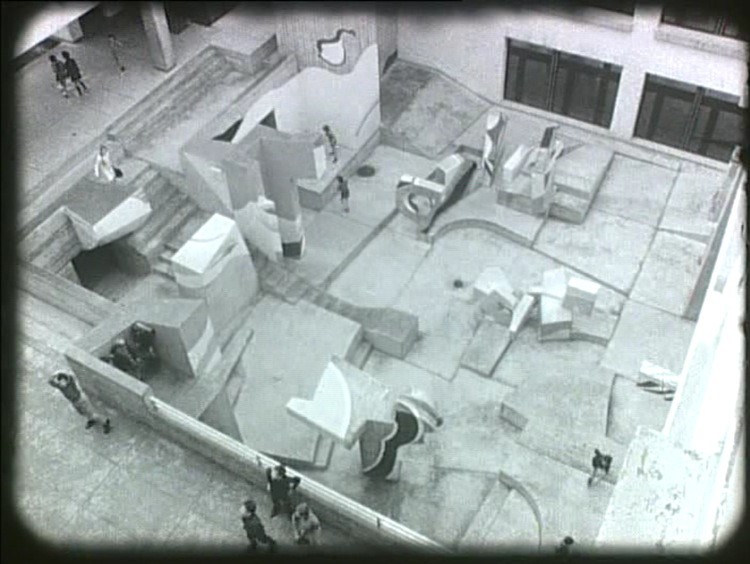

Film stills:

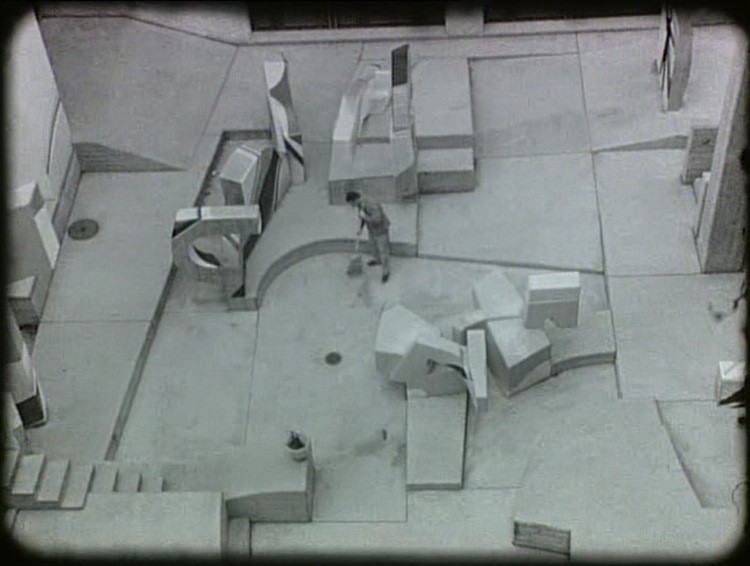

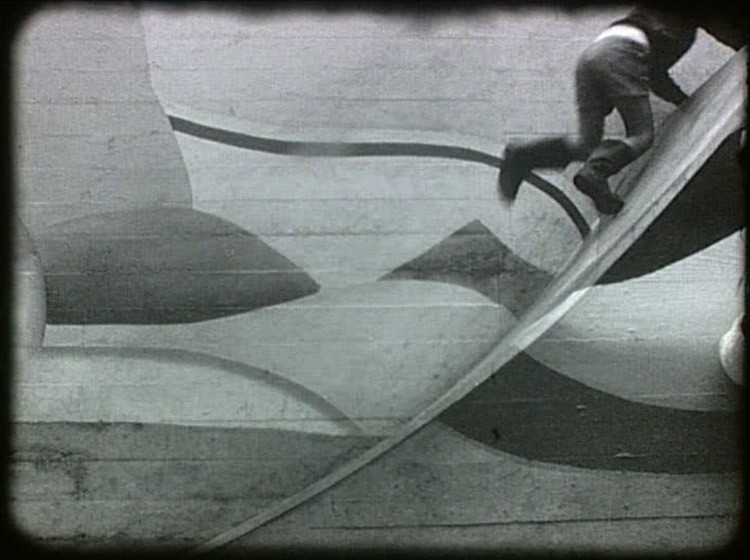

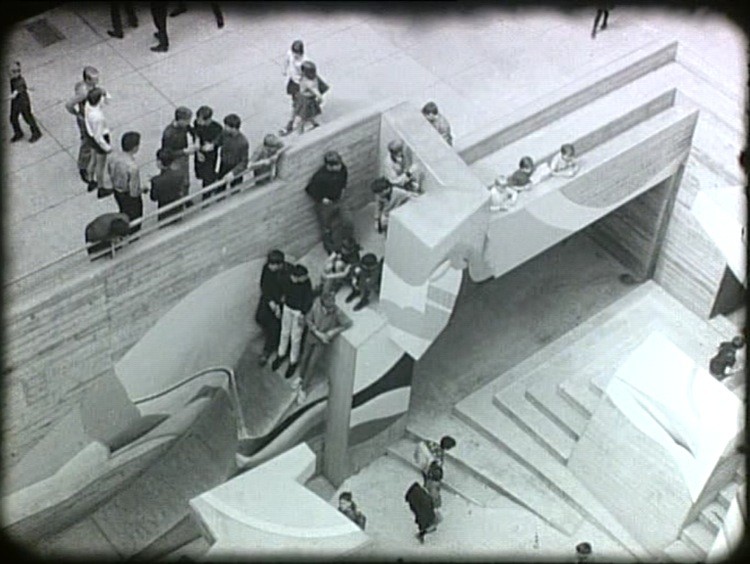

Stills from «Georg Radanovicz sieht die Pausenhofplastik Reinach» (b/w, 6 min. 52, 1968) by Georg Radanovicz on Michael Grossert’s Playground for Aumatten Primary School in Reinach, Switzerland.

Review E-Flux, september 8 2010

Michael Grossert’s „3 Playgrounds, 1967–1975“ at New Jerseyy, Switzerland

6 Aug – 28 Aug 2010

It can be difficult in our age of post-everything to comprehend the political import and impact of art and architecture in the 20th century, when stakes—see: two world wars, and the modernist and/or progressive ardor that arose around them—were high. It is far easier in our climate, in which art and politics often feel like estranged commuters, to understand such work as part of a formalist or art-historical continuum. An exception might be the experimental, postwar playgrounds of America and Europe—as designed by artists, pedagogues, and innovators like Isamu Noguchi, Aldo van Eyck, and Carl Theodor Sørensen—which even now retain a tangible weirdness and palpable utopian spirit. That playgrounds are a social project is a given, even when designed by artists with „purely“ aesthetic intentions.

If Noguchi’s unrealized „Play Mountain“ (1933) united modernist sculptural principles and Japanese design—Noguchi felt it was the „progenitor of playgrounds as sculptural landscapes“—and Aldo Van Eyck employed the formalism of the De Stijl artists in the 700 postwar playgrounds he designed in Amsterdam, the Basel sculptor Michael Grossert’s contribution to the field appears small indeed. It constitutes just three projects—one unrealized—made between 1967 and 1975. Nevertheless, these playgrounds, as seen in video, photographs, models, and prototypes, provide an incommensurate amount of pleasure in the wonderfully surprising show at New Jerseyy devoted to them.

Grossert’s first playground, in 1967, came about when he was forty years old, as the result of an ongoing conversation with architect Ruedi Meyer about the relationship between architecture and abstract sculpture. Made for Meyer’s primary school in Reinach, just outside Basel, Grossert’s „walk-in sculpture“ features both swooping and angular concrete forms—a marriage of Barbara Hepworth curviness to jutting, Picasso-ish planes—painted in Mediterranean blues and yellows and graphic washes of white. An old black-and-white video on view, conjuring an Italian neorealist film, reveals children swarming the structure, while large photographs reveal its brilliant (and recently restored) coloration.

Grossert’s second project, in 1971, was a „climbing sculpture“ for a Basel development. The work featured thirty yellow, red, and blue polyester sculptural elements—at once propeller-like and prescient of Transformer figurines—that were stackable. Half were fixed into place; the rest were left for children to move as they pleased. Several of these lightweight components sit casually on the gallery floor. Pebbled and dirty, they elicit both a modernist sculptural frisson and a bit of childlike excitement: they are obviously meant to be in some field, tumbled about. The sculptor’s final playground, in 1974, came to naught. The model on view, for a project in France, employs the bright, painterly hues of his first playground, and the propeller-like forms of his second. That it was never built is perhaps indicative of the larger playground movement, which was quickly losing steam.

The playgrounds I grew up with in California in the 1980s were sad affairs: either attenuated metal skeletons or bulbous blue-and-orange plastic volumes that quickly dulled. Likewise, Basel’s playgrounds have mostly become regulated, inoffensive structures. While the relationship between sculpture and architecture is still fervently being explored, it is worth wondering why the works that emerge from that conversation are more often illustrious museums or art pavilions than utilitarian playgrounds. If this has something to do with a stemming of pedagogical ardor in this century, it is still—take a look at your neighborhood playground—a shame. As Grossert himself said, his projects realized the idea of the „walk-in sculpture“ that occupied him for years. Such ideas have neither flagged nor left the minds of our artists, but they are now usually called installations, their province is the museum or gallery, and their population has usually left play far, far behind.

—Quinn Latimer