The beginning of the playground movement in the United States

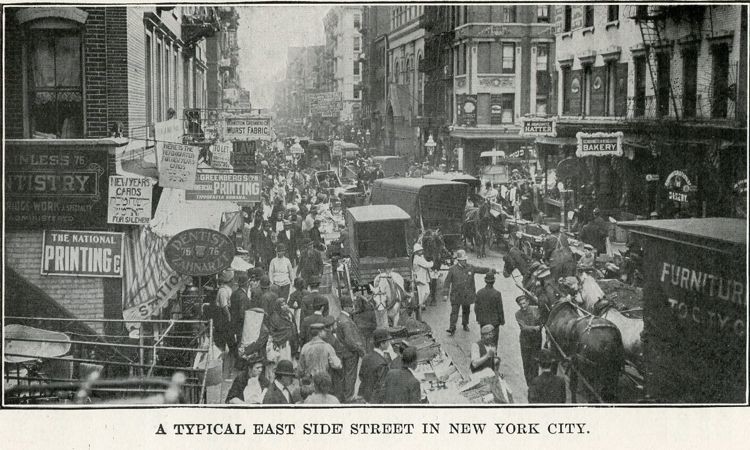

During the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century and into early decades of the twentieth century, immigration from many countries and rural American resulted in massive pockets of poverty in America’s largest cities. In these ruthless slums thousands of homeless children lived and fought to survive in streets under demeaning, sadistic conditions. (Zacks, 2012). A New York City law prohibited playing in the streets and thousands of children were hauled into court. (Brace, 1889: Riis, 1890, 1902, People’s Institute, 1910). Gulick, 1920; Frost, 2010).

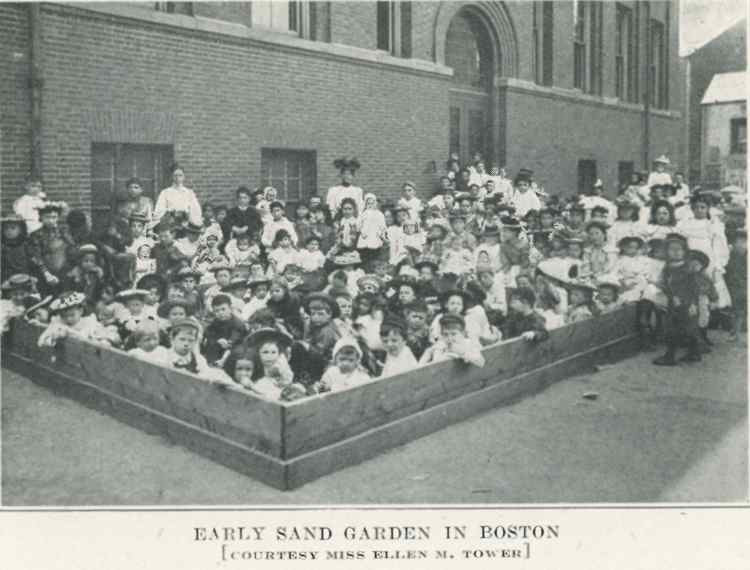

The the Massachusetts Emergency and Hygiene Association and their Sand gardens in Boston

The origin of the play movement are the sand gardens in Boston. Dr. Marie E. Zakrsewska, while visiting in Berlin during the Summer 1885, observed heaps of sand in the public parks in which the children of the rich and the poor were permitted to play under the supervision of the police. As a result of her report to the chairwoman of the executive committee of the Massachusetts Emergency and Hygiene Association (MEHA), a large heap of sand was placed in the yards of the Parmenter Street Chapel and the West End Nursery. At the Parmenter Street Chapel, an average of 15 children attended three days a week during July and August 1885, under the guidance of a lady living in the neighborhood. The number of sand piles increased in the following years, located in school yards and the courts of tenement houses. In 1893, a superintendent of all sand gardens with kindergarteners located at each, were employed. Digging instruments and building blocks were furnished. By 1899, the MEHA run 21 sand gardens. (Rainwater, p. 22-23)

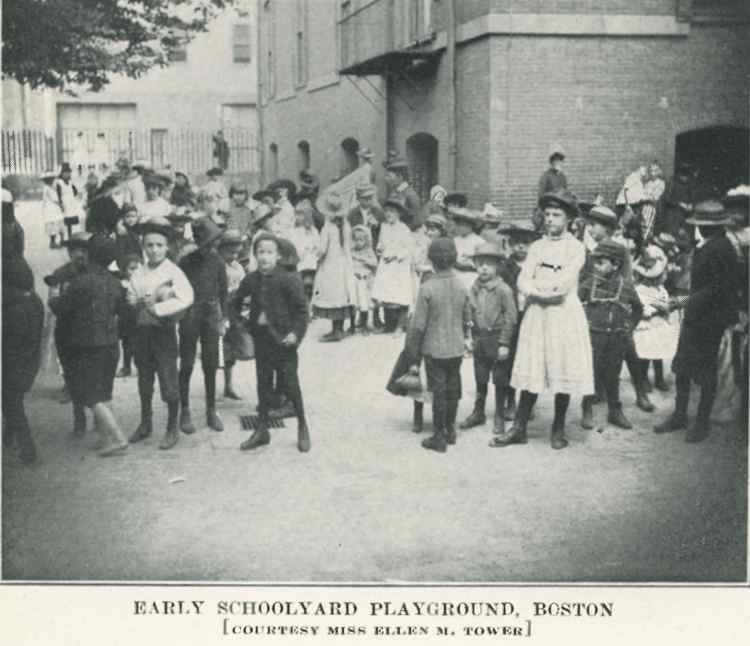

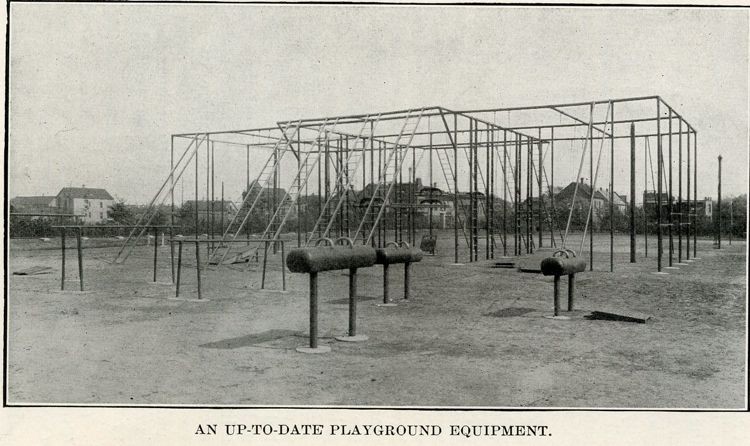

The Park Department in Boston entrusted the management of other play facilities to the Association: a vacant lot for playground uses and a Outdoor Gymnasium, in 1889 (boys) and 1891 (girls). The Outdoor Gymnasium was fenced and equipped with swings, ladders, see-saws, running track, wading, rowing and bathing facilities. (Rainwater 28)

The idea of constructing small squares and playground was incorporated in the plan of the Metropolitan Park Commission of Boston in 1893 (Rainwater 35).

Other cities – Philadelphia, Providence, New York, Baltimore, Brooklyn, Chicago, Newark, Worcester, Portland – followed the example: local charities installed sand gardens and open air gymnasiums in these cities before the turn of the century. Miss Ellen M. Tower, chairwoman of the Playground Committee of MEHA gave lectures in several US cities on the subject. (Rainwater 42)

After the sand gardens for infants opened during the Summer months, the movement provided so called „model playgrounds“ for children and youths under the supervision of a kindergartener and a policeman, and later „small parks“, the first attempt in the US for playground landscaping, and also the first attempt to provide an all-year provision of play and recreation. The City of Chicago pioneered to set up recreation centers with indoor and outdoor play and recreation facilities for the entire community, opened all-year. Such a center with a „field house“ first opened in 1905 with the intention to favor active play and recreation over passive pleasure. (Rainwater 93-104).

The Playground movement was well organized on a national level: The National Recreation Association was founded in 1906 as the Playground Association of America (PAA) by eighteen men and women from playground associations, public school and municipal recreation departments, settlements, teachers’ colleges, the kindergarten movement, and charity organizations. Initially, PAA was funded by private sources and volunteers until the Russell Sage Foundation agreed to help fund services and start up costs.

The organization was dedicated to improving the human environment through park, recreation, and leisure opportunities. Its concept of recreation evolved from the development of supervised playgrounds to one that includes a broad range of leisure-time programs. Reflecting the organization’s changing mission, it changed its name to the Playground and Recreation Association of America (1911-1930)

„It is worse than useless to attempt to conduct playgrounds without supervisors. Important as play may be from the standpoint of health and recreation, it is far more important in its social aspects. It is the school for citizenship, the laboratory where habits are developed that are all important.

[…]; therefore, we must have play under right conditions, and the city street is not likely to furnish such conditions, nor is the freedom of the country sure to do so. The properly supervised playground is the solution of the problem. […] Children may learn much from precept, but habits of honesty, loyalty, and fair play that become a real part of the character can be secured only through practice, and a well supervised playground is a safe place in which to practice.“

Lee F. Hammer, First Steps in Organizing Playgrounds, New York, 1908, p. 24.

With the start of World War I, the Recreation Association of America (PRAA) expanded to provide services to troops at training camps. Due to poor physical fitness results of prospective recruits, fitness became a large concern in America. The entire post-war decade was one of large growth for the PRAA. In the mid-30s, the name of the organization changed to the National Recreation Association (NRA), reflecting its efforts to increase support for and broaden the definition of recreation and leisure.

During the depression, the NRA cut back and, by the end of World War II, many government programs took over the majority of the recreation activities.

Episode of creative play

In 1950, a new concept brought from Europe, was for the first time introduced in the U.S.: the „Junk“ Playground. McCall’s Magazine funded such a project, called „The Yard“, in Minneapolis. Supervised by Margaret Barry Settlement House, a community center, its aim was „to stimulate creative play so that the children can learn the basic process of living while playing“ . It was opened and financed for a twelve-month period by McCall’s Magazine as its contribution to the Midcentury White House Conference on Children and Youth. (Benjamin 24)

Sources:

Joe Frost: Evolution of American playgrounds

Regents of the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, and the University Libraries; https://special.lib.umn.edu/findaid/xml/sw0074.xml, retrieved 1/6/2013

Lee F. Hammer, First Steps in Organizing Playgrounds, New York, 1908, p. 24.

Benjamin, Joe. In Search of Adventure: A Study in Play Leadership. London: National Council of Social Service, 1966

Clarence Elmer Rainwater: The Play Movement in the United States, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1921.

Links:

Joe Frost: Evolution of American playgrounds

Playgrounds and Public Recreation (1898–1929)

Update: March 22, 2018

Early Schoolyard Playground, Boston (source Rainwater)

Early Sand Garden in Boston (source Rainwater)

up-to-date playground equipment, source: Lee F. Hammer, 1908

East side street New York City, source: Lee F. Hammer, 1908

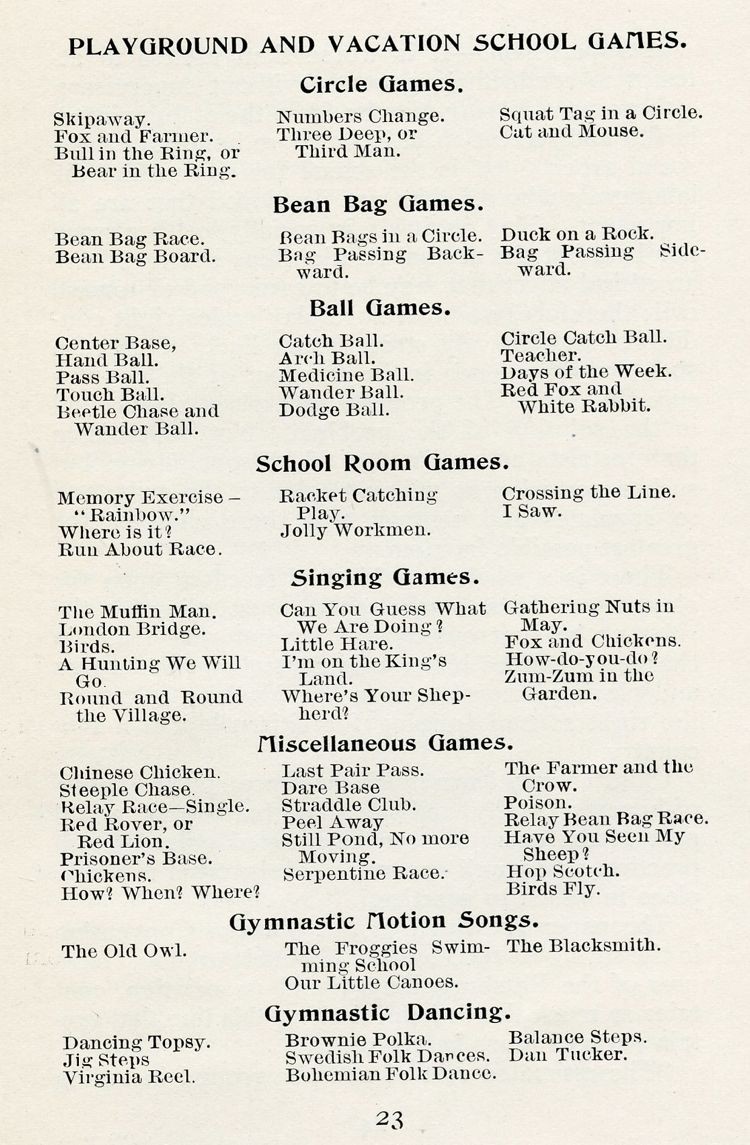

Children Games, source: Lee F. Hammer, 1908