M. Paul Friedberg (1931-2025), Landschaftsarchitekt, New York

M. Paul Friedberg kommt als junger Baumschulgärtner nach New York, wo er 1958 sein eigenes Büro eröffnet. Auf dem Gebiet der Landschaftsarchitektur noch unerfahren, kann er jedoch erste Aufträge der New York Housing Authority, der Behörde für gemeinnützigen Wohnungsbau, akquirieren. Die strengen Reglemente erlauben dabei kaum Gestaltungsfreiheit. Es gelingt Friedberg jedoch eine Bresche zu finden: Anstelle der geforderten Statue bei den Nathan Straus Houses schafft er einen kleinen öffentlichen Platz und beauftragt zudem kurzerhand einen befreundeten Künstler, statt der Büste eine Skulptur zu entwerfen, auf der Kinder spielen können. „Die Tatsache, dass ich das System herausgefordert hatte und damit erfolgreich war, gab mir den Anreiz, mit einer erweiterten Perspektive an künftige Arbeiten heranzugehen. Dieses Spiel der Genugtuung durch die Austestung traditioneller Grenzen, des ‚Status quo‘.“

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), dem meistdiskutierten Werk zur Stadtplanung, kritisiert die Journalistin und Aktivistin Jane Jacobs die städtische Behörde, die Slums saniert, indem sie deren Bewohner in riesige Sozialwohnungssiedlungen umquartiert. Betroffen vom Befund des Buches wendet sich die visionäre Philanthropin und Präsidentin der Vincent Astor Foundation, Brooke Astor, an die Housing Authority. Brooke ist bemüht, der Stiftung ein neues philanthropisches Profil zu verleihen und bietet Unterstützung an, die ghettoartige Situation der Wohnblocks zu verbessern. Ihr Idealbild sind „grüne Aussenräume“, die als Treffpunkte für verschiedene Gruppen von Bewohnern wie Kinder, Jugendliche und Senioren fungieren. Friedberg gewinnt den Wettbewerb für das erste Projekt, die Gestaltung einer besseren Umgebung für die Carver Houses in Spanish Harlem, Manhattan. Dabei hat er vollkommene Gestaltungsfreiheit. Er projektiert eine Spiellandschaft, in der die Topografie das zentrale Spielmoment bildet. Er wagt jedoch noch nicht, das Konzept radikal zu Ende zu führen und bestückt die Landschaft zusätzlich mit vorgefertigten Spielgeräten.

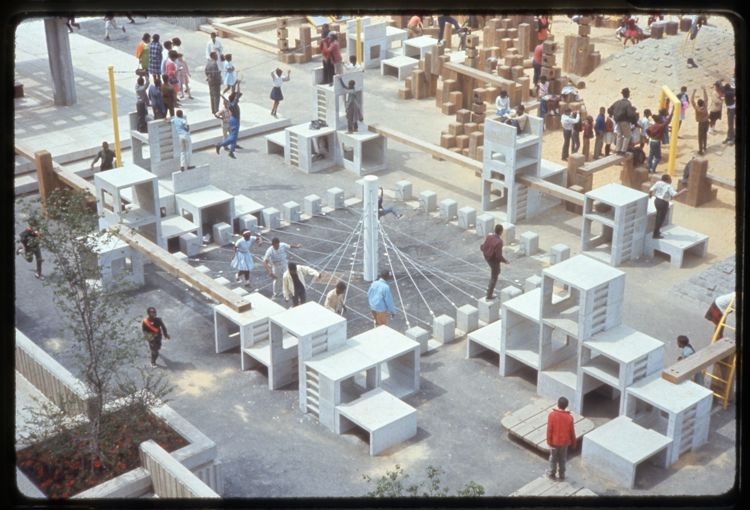

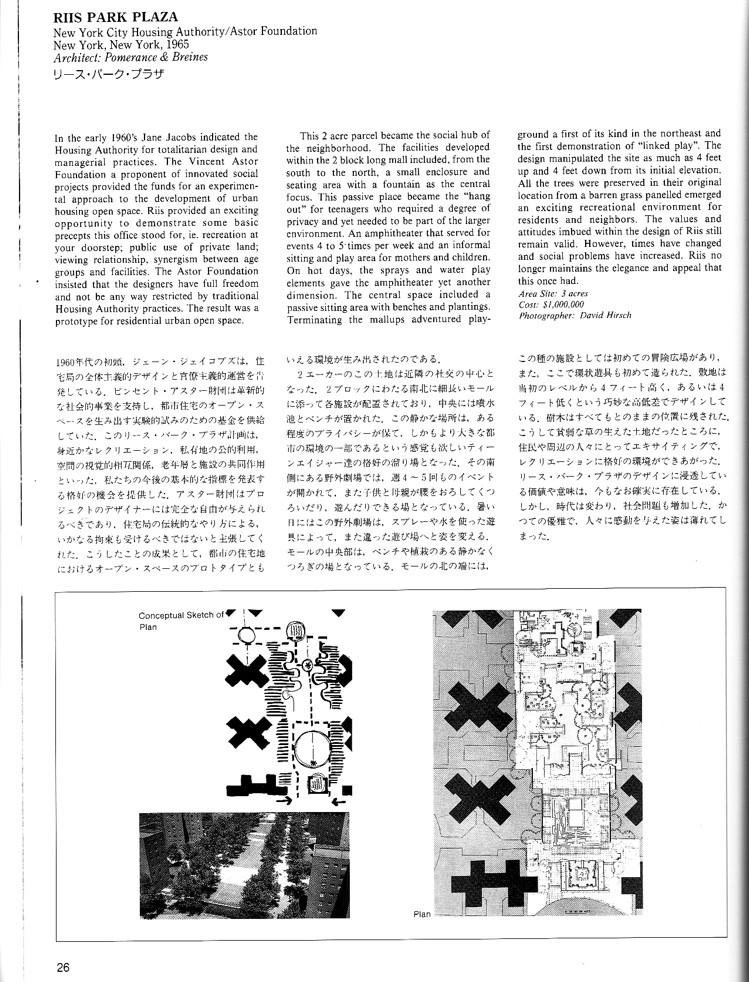

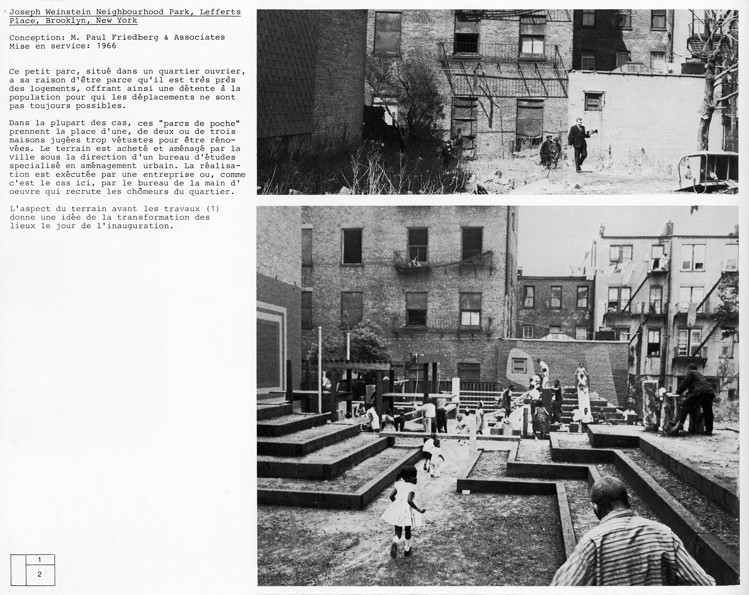

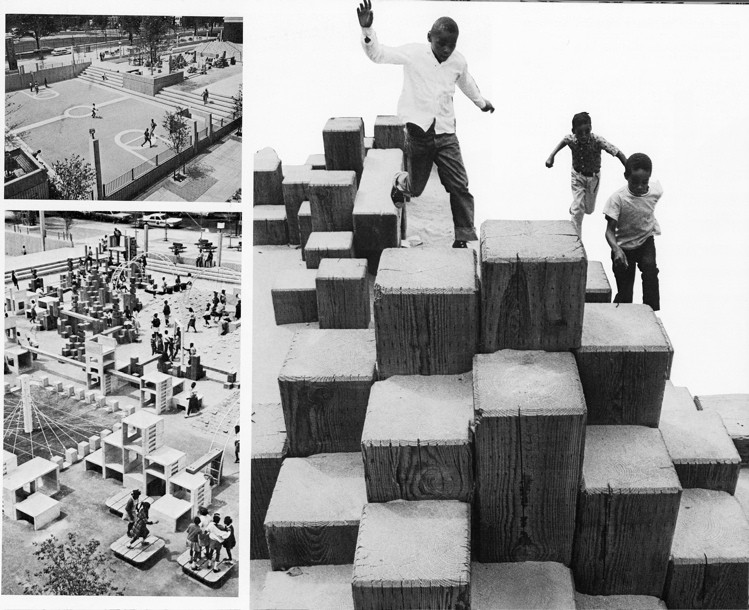

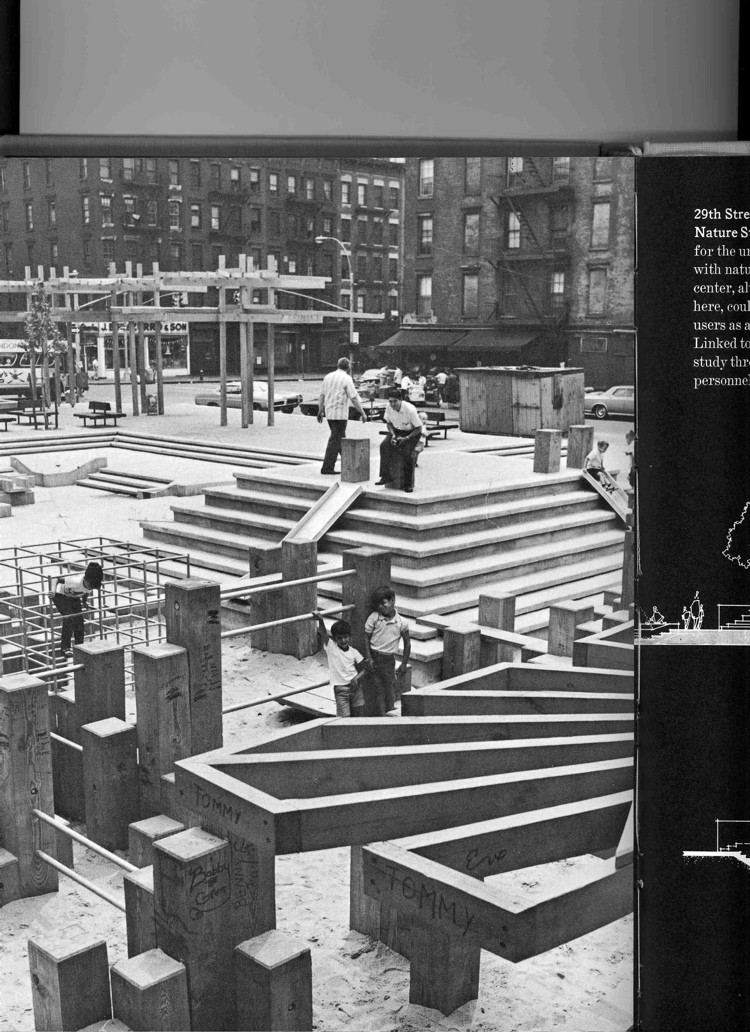

Erst beim nächsten Entwurf für die Jacob Riis Houses im East Village vertraut er voll dem Potential der Topografie: Es entsteht eine Art Berglandschaft aus Pflastersteinen, Beton- und Holzskulpturen, einem Amphitheater und zahlreichen Sitzgelegenheiten. Friedberg nennt sein Vorgehen, das er 1970 in der Publikation Play and Interplay vorstellt, „Linked Play“: „Wir begannen den Wert vom sogenannten ‚Linked Play‘ zu erkennen. Der Spielplatz wurde zur Umgebung und alles auf dem Spielplatz war Teil dieser Umgebung… aber er hatte nicht das, was ein Spielplatz normalerweise haben sollte: lose Elemente, die die Kinder selber kontrollieren.“ Die Neugestaltung des Aussenraumes der Riis Houses erregt grosse Aufmerksamkeit und Friedberg erhält zahlreiche Auszeichnungen.

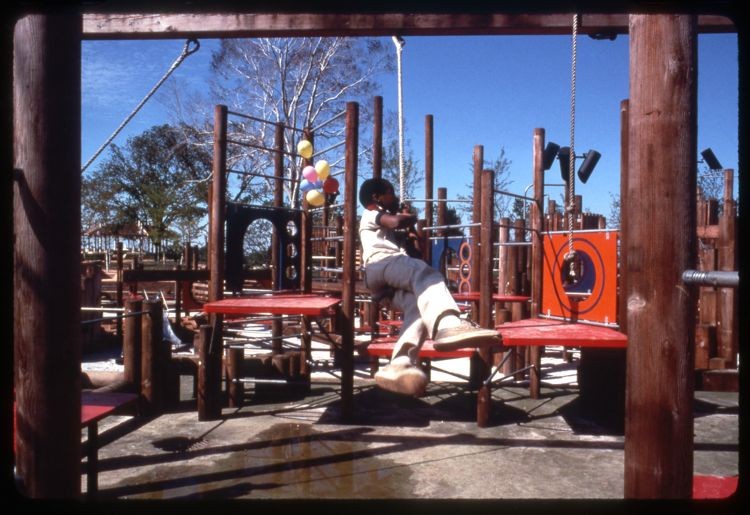

Wie für Richard Dattner sind auch für Friedberg die Abenteuerspielplätze Londons und die nie gebauten Spiellandschaften Isamu Noguchis wichtige Wegweiser. Zentral ist zudem die unmittelbare Stadtumgebung, die Friedberg als vielfältige Inspirationsquelle dient. Als er beim Bau der New Yorker Subway vertikal in den Boden gerammte Holzpfosten sieht, übernimmt er die Idee. Es entstehen daraus

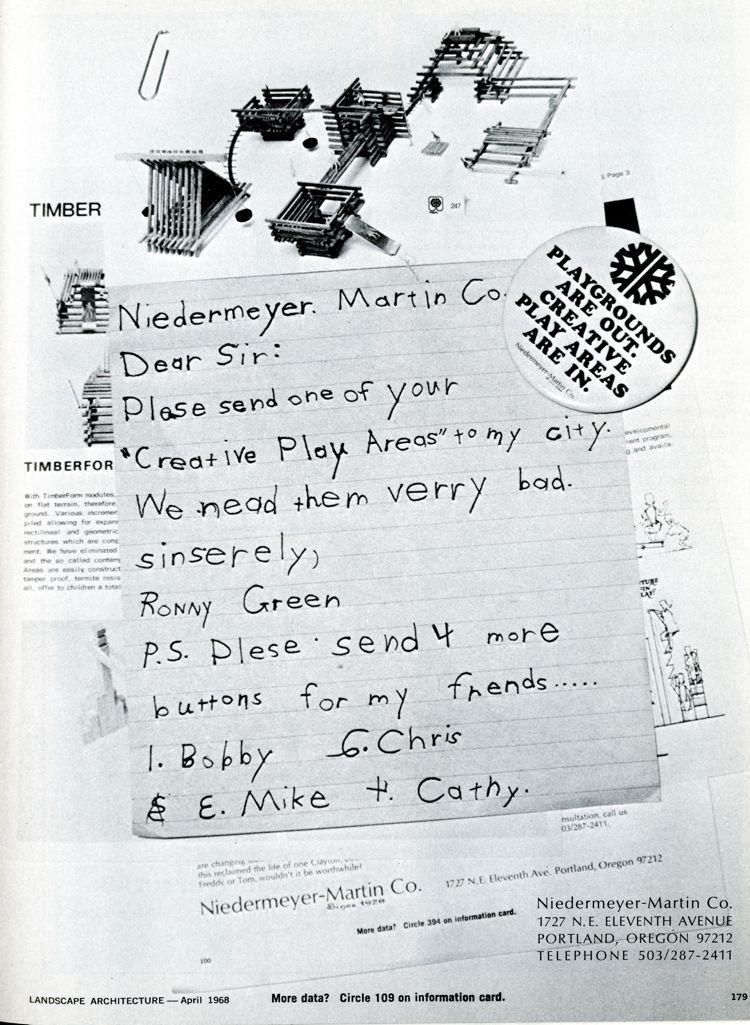

Klettergerüste mit angehängten Schaukeln. Dazu entwirft er mobile Spielplatzmodule, mit denen leere Grundstücke vorübergehend in Spielplätze – zu Vest Pocket Parks – umgewandelt werden. Die dazu benötigten Holzpfosten werden aus Portland angeliefert. Als die Nachfrage nach dieser Art von einfacher

Gestaltung zunimmt, gründet Friedberg zusammen mit Ron Greene, dem Grafiker der Holzfirma in Portland, die Firma Timberform. Zusammen entwerfen sie Modelle für Holzspielplätze, die je nach Ort und Budget einfach realisiert werden können: Ein Set von Holzpfosten kann bestellt und dann selbst zusammengebaut werden, sei es nach einer mitgelieferten Vorlage oder nach eigenen Vorstellungen. So entstehen zahlreiche Spielplätze in den ganzen USA.

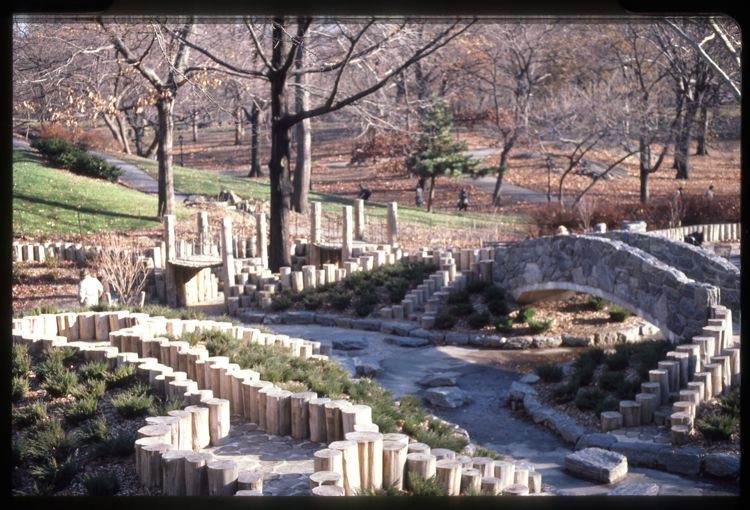

Friedberg führt seine Karriere als Landschaftsarchitekt fort und entwirft bis in die 1980er Jahre gelegentlich noch Spielplätze. Anstelle von „reinen“ Spielräumen für Kinder schafft er Stadtlandschaften, die Spiel, Raum- und Sinneswahrnehmungen einbeziehen.

©Gabriela Burkhalter

M. Paul Friedberg (1931-2025), landscape architect, New York

M. Paul Friedberg arrived in New York in 1958 to set up shop as a young nursery gardener. Although he had no experience in landscape architecture, he still managed to win his first commissions from the New York Housing Authority, which was responsible for building public housing. The strict regulations offered hardly any room for creative design. Yet Friedberg managed to find a gap in them: instead of the statue planned for the Nathan Straus Houses, he designed a small public square; then, at short notice, he even asked an artist friend to make a sculpture for children to play on instead of a bust. “The fact that I had challenged the system, and been successful, gave me an incentive to approach future work with a broader perspective. The satisfaction came from pressing the limits of traditional boundaries, the ‘status quo.’”

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), the most controversial book on urban planning, the journalist and activist Jane Jacobs criticized urban authorities for renovating slums by relocating their residents to giant public housing projects. Brooke Astor, a visionary philanthropist who was president of the Vincent Astor Foundation, was so struck by the book’s claims that she turned to the Housing Authority. In what was also an attempt to give the foundation a new philanthropic profile, she offered to help improve the ghetto-like situation in the projects. Her ideal image was “green outdoor spaces” that could serve as meeting places for a wide range of residents, from children and teenagers to seniors. Friedberg won the first competition to design a better environment for the Carver Houses in Spanish Harlem in Manhattan, and was given complete freedom for the project. He came up with a landscape whose topography was the main feature to play in and with; however, he did not make the project that radical after all and ended up equipping the landscape with prefabricated playground equipment.

Only with his next design, for the Jacob Riis Houses in the East Village, did he fully trust the potential of topography and produce a kind of hilly landscape of paving stones, concrete and wooden sculptures, an amphitheater, and numerous places to sit. Friedberg called this approach “Linked Play,” as he described it in his 1970 book Play and Interplay: “We began to see the value of something called linked play. The playground became an environment and everything in the playground was a part of that environment … but it didn’t have what a playground really should have: loose elements that kids control themselves.” The new design of the outdoor spaces at Riis Houses attracted a great deal of attention, and Friedberg received numerous awards.

For Friedberg, like Richard Dattner, the adventure playgrounds in London, and Isamu Noguchi’s unrealized playground designs for New York were important inspirations. In addition, the immediate urban environment was central; it served Friedberg as a versatile source of ideas. When he saw wooden posts hammered vertically into the ground at a subway construction site, he adapted the idea and created jungle gyms with swings hung on them. He also designed mobile playground modules that could turn vacant lots into temporary playgrounds: “Vest Pocket Parks.” The wooden posts needed for these were delivered from Portland. As the demand for this kind of simple design grew, Friedberg and Ron Greene, the graphic designer at the lumber company in Portland, founded Timberform. Together, they designed models for playgrounds made of wood that were easy to adapt to a playground’s site and budget: you could order a set of wooden posts and then install them yourself, according to either the company’s plans or your own ideas. Numerous playgrounds thus sprang up all over the United States. Friedberg continued his career as a landscape architect and even occasionally built playgrounds in the 1980s. Instead of “pure” play spaces for children, he created urban landscapes that incorporated play, space, and the senses.

©Gabriela Burkhalter

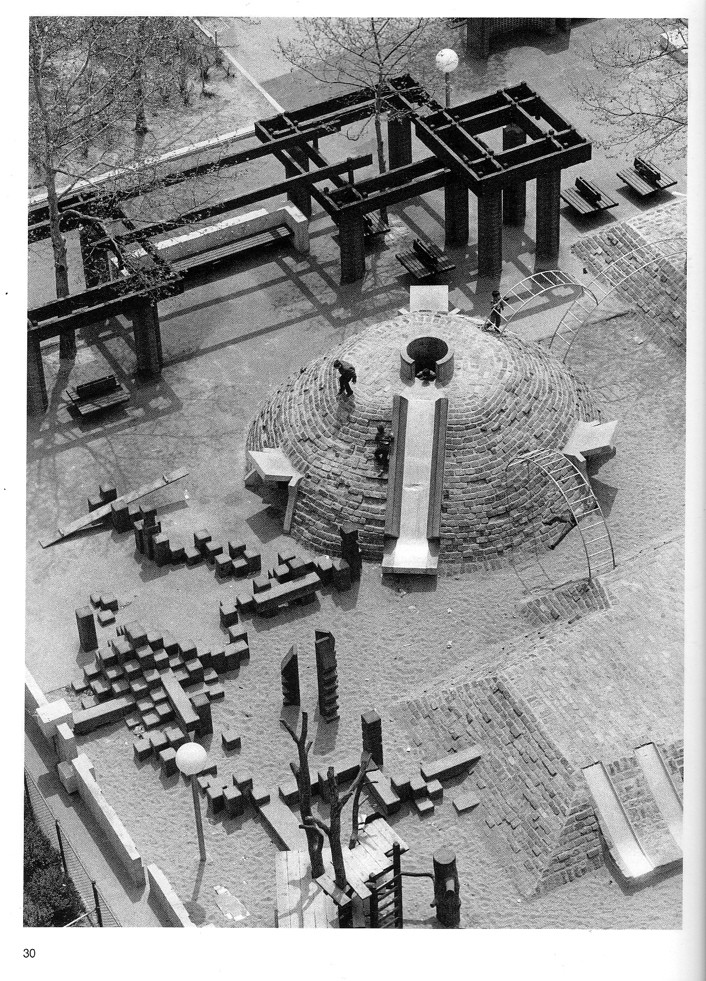

Play environments for housing projects, schools, vest pocket parks:

– Nathan Strauss Houses

– Quincy street (together with Pratt Institute)

– Carver Houses (1963), Astor Foundation

– Leffert Place Brooklyn, Rockefeller Foundation (1964), Vest Pocket Park

– Riverview Towers at 140th Street (Manhatten)

– Jacob Riis Plaza in the Lower East Side (1965), Astor Foundation

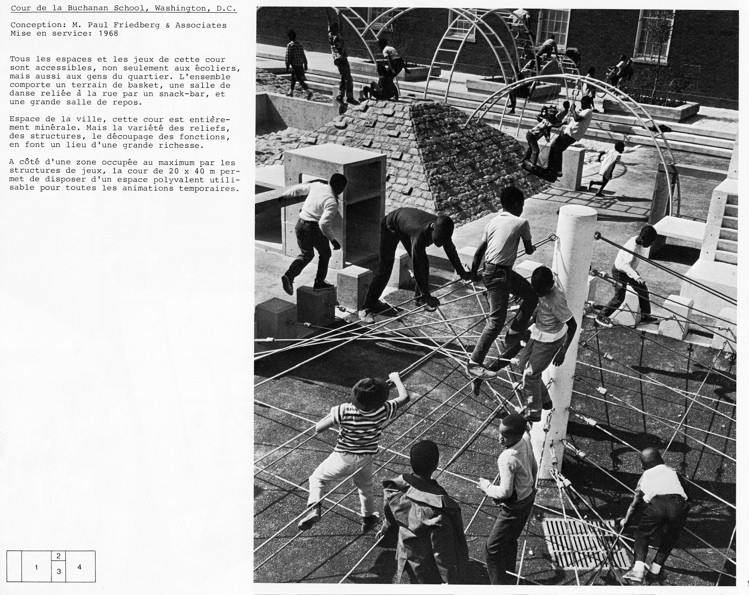

– Buchanan School (Washington D.C.)(1966), Astor Foundation for Lady Bird Johnson’s Beautify America Program

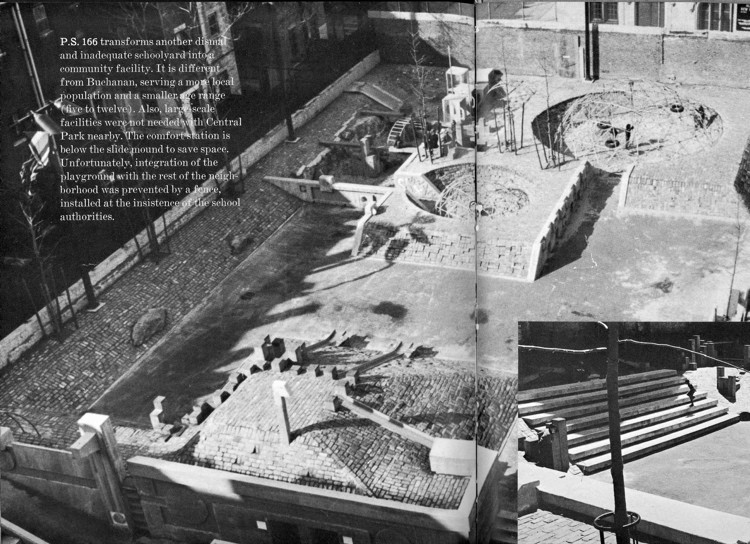

– P.S. 166 on West Eighty-ninth Street (Manhattan) (1967), 1986 renamed Playground 89. Rebuilt in 1999 in the spirit of the old design.

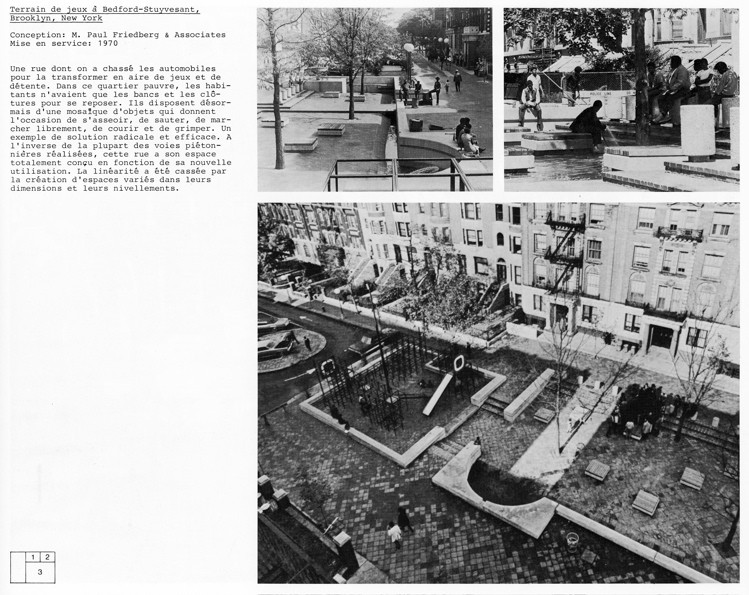

– A series of ten Vest Pocket Parks 1967-1968: Bedford Stuyvesant (Brooklyn), Mulberry Street Park, 29th Street

– Housing and Urban Development Demonstration Grant (Grant from the Department of Housing and Development; Beautification Act) (1968)

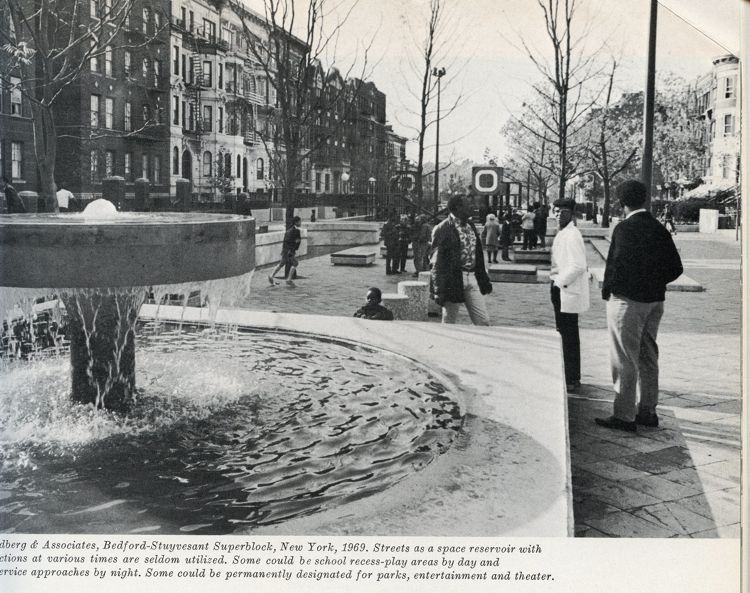

– Superblock Bedford-Stuyvesant, architect: I.M. Pei (1969)

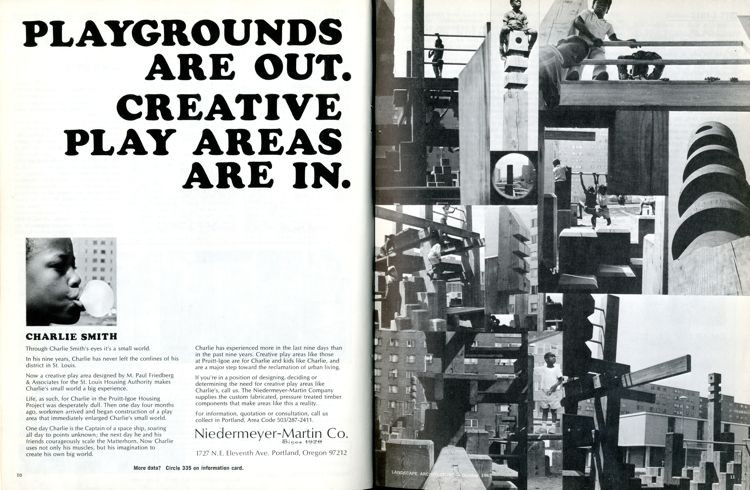

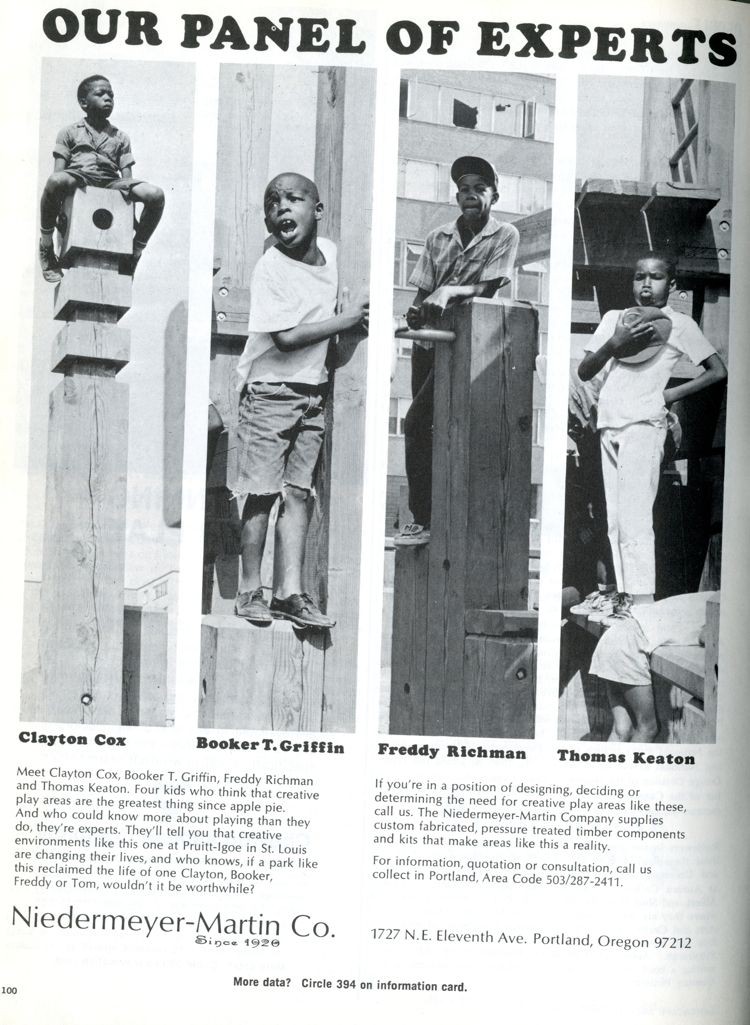

– Playground for Housing Project Pruitt-Igoe, St. Louis (produced by Timberform, Oregon) (1968)

– Gottesman Plaza Playground on West Ninety-fourth Street (1970)

– Playground for Fort Lincoln Urban Renewal Plan, Washington, D.C. / Fort Lincoln New Town (1972)

– Billy Johnson Playground at East 67th Playground, Central Park (1985)

superblock Bedford-Stuyvesant, I.M. Pei; „Epic to Ad Hoc: I.M. Pei and M. Paul Friedberg’s Bedford Stuyvesant Superblock“

Excerpt from M. Paul Friedberg Oral History Interview

New York City Department of Parks & Recreation: Playground 89

Playground Battles: Can Safety and Adventure Co-Exist Where Children Play? By Kim Velsey, Observer 8/13/2015

M. Paul Friedberg, in The Cultural Landscape Foundation

M. Paul Friedberg: „Is This Our Utopia ?“, in: Bettelheim, Bruno, Wolf von Eckardt, M. Paul Friedberg, Lee Rainwater, and Eddie N. Williams. 1971. The social impact of urban design. [Chicago]: Center for Policy Study, University of Chicago.

Source text and images

Solomon, Susan G. American Playgrounds: Revitalizing Community Space. Hanover [N.H.: University Press of New England, 2005.

Alison Dalton, M. Paul Friedberg’s Early Design in New York City in, Birnbaum, Charles A. Preserving Modern Landscape Architecture: Papers from the Wave Hill-National Park Service Conference. Cambridge, Mass: Spacemaker Press, 1999, 57-58.

M. Paul Friedberg: Play and Interplay, 1970, The Macmillan Company, New York

M. Paul Friedberg: Process Architecture No. 82, 1989.

Marguerite Rouard, Jacques Simon: Espaces de jeux : de la boîte à sable au terrain d’aventure, D. Vincent, Paris 1976.

Peter Wolf. „The urban street“ (A provocative forum in Minneapolis points up the unrealized potential of our long-neglected streets and their effect ont the quality of life.), Art in America Nov/Dec. 1970.

Landscape Architecture Quarterly (LAQ): October 1968.

color images: courtesy M. Paul Friedberg

update: 5/1/2013, September 15, 2013, September 2014, July 2019, September 2023

Jacob Riis House, New York, 1966

Jacob Riis House, New York, 1966

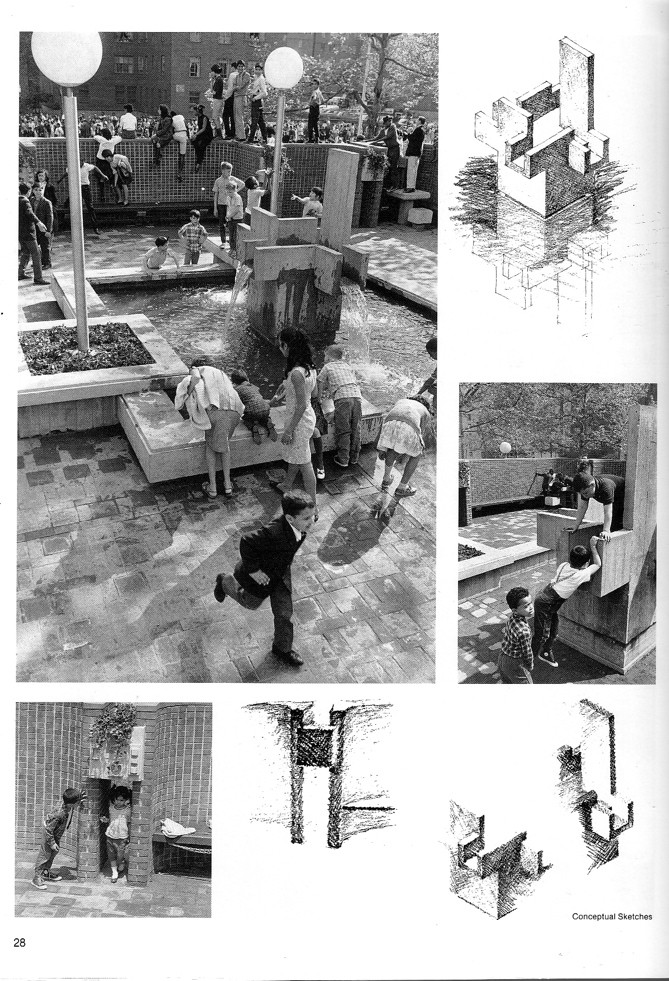

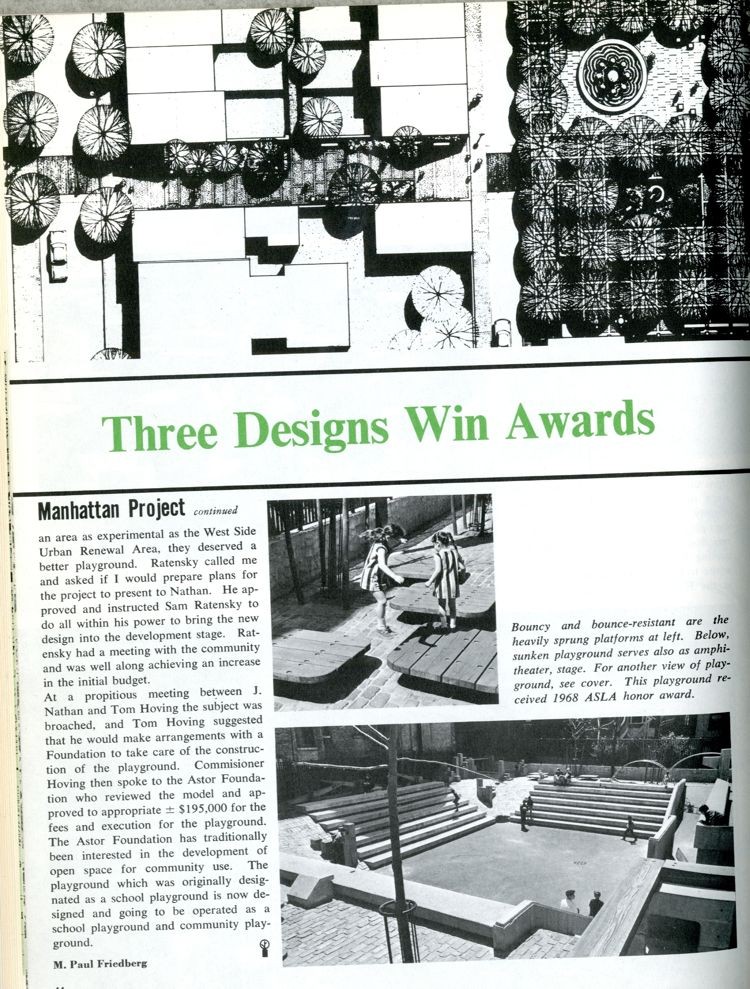

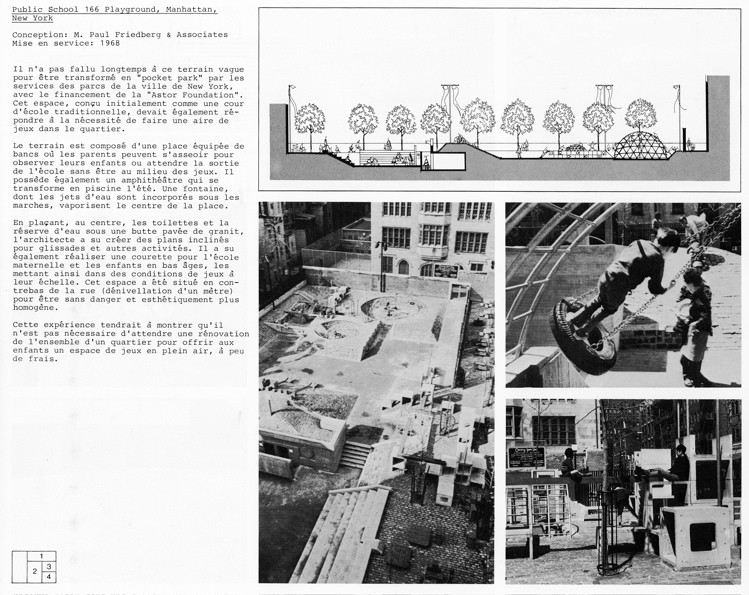

Manhattan Project: PS 166, LAQ, oct. 1968

Manhattan Project: PS 166, LAQ, Oct. 1968

P.S. 166, New York, schoolyard

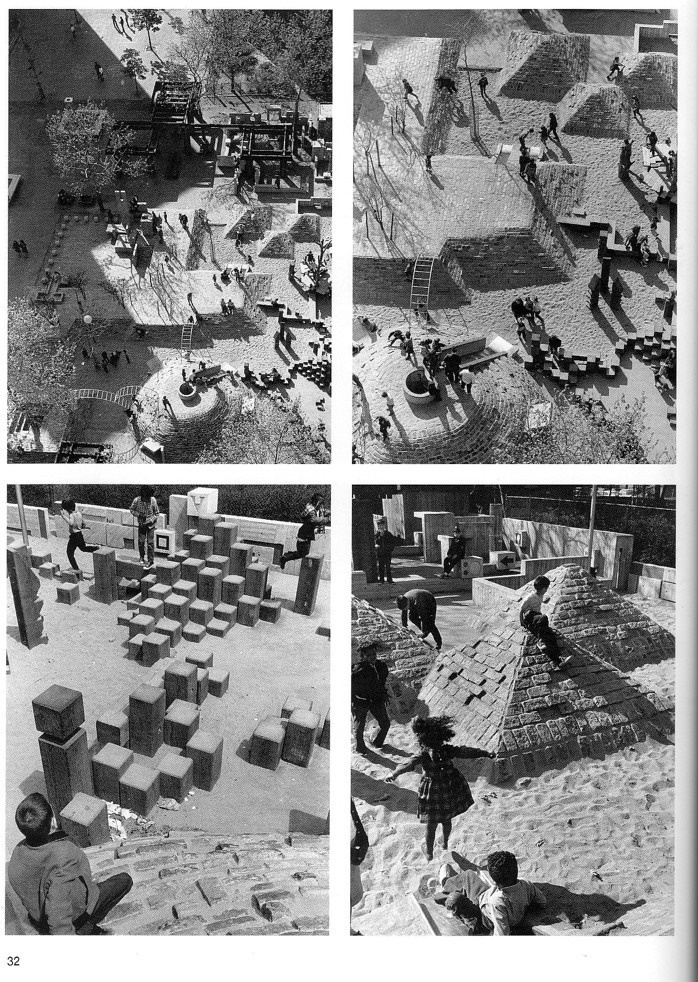

Playground Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, New York, 1969

street-playground, 1969 Bedford-Stuyvesant (Art in America)

Public School 166 Playground, Manhattan, New York, 1968

Advertisement Timberform for Pruitt Igoe, LAQ 1968

Advertisement Timberform for Pruitt Igoe, LAQ 1968

Advertisement Timberform for Pruitt Igoe, LAQ 1968

29th Street Vest Pocket Park, NY

Fort Lincoln Urban Renewal Plan, Washington, D.C. Fort Lincoln, 1972

Billy Johnson Playground, Central Park, New York City, 1985