Housing Policy in Sweden

When the Social Democrats came to power in 1932, they took action against the bad living conditions in some urban areas, among the badest housing conditions in Europe. This was based on fears that bad housing conditions was causing a serious decline in polulation. In 1934, the eminent sociologists Gunnar and Alva Myrdal published „Crisis in the Population Question“ (Kris i befolkningsfrågan), who discussed the declining birthrate in Sweden and proposed possible solutions. The book was influential in the debate that created the Swedish welfare model and public housing policy (Worpole 76, wikipedia).

As a consequence a Social Housing Commission was set up in 1933. A large programm of municipal house building in a functionalist style began, commonly of median-rise apartment blocks with bathrooms and balconies, popularly known as „Myrdal tenements“ and a large estate of modern villas was developed in Stockholm near lake Mälaren, between 1934 and 1939 (Worpole 76).

Planning Stockholm after Word War II

Sweden emerged unharmed by World War II, and entered a period of economic and social prosperity, but the housing situation was difficult because Sweden shifted from a rural to an urban and industralized society.

In 1941, the Council of Stockholm decided to build the subway system and to give an impulse to the restructuring of the capital (Treib 5).

In 1945, a manifesto of planning established principles for a radical renovation of Stockholm city center and for the development of extensive suburban developments. They promoted the Swedish Welfare State, the „Folkhemmet“ (people’s home) and new towns, so-called ABC towns (A=arbete/ work, B=bo/housing, C=Centrum/public and commercial service), inspired by the Postwar English new towns. During the late 1940s, few countries had a similar engagement with modern social ideas and their architectural equivalent (Treib 4).

Vällingby (8 miles West from Stockholm), inaugurated in 1954, was the first ABC town. The central place was designed by Erik Glemme. This masterpiece of planning brought international attention and praise (Treib 11).

Until the 1960s, this architectural mouvement to produce a healthy and human living environment was called functionalism. In the late 1960s, the building industry became more industrialized, size and form of the buildings was increasingly inhuman and monoton.

Urban recreation and play

Under Holger Blum, Stockholm’s Parks commissioner from 1938 to 1971, city parks received a new form and function: they were laid out as a network infiltrating the city, and served as outdoor living room for everyday life.

Parks were regarded as

– active and essential urban elements,

– as indivisible parts of the social housig program.

For the first time, landscapes were planned for active use by the general public.

The important number of city parks designed by the municipal park department became renowed for their heigh quality and were refered to as „Stockholm school“ of Park Design.

The revolution in urban recreation and play that spread accross Europe came from Scandinavia, during and after the war, partly through Sørensen’s development of the Junk Playground, but principally through the energetic efforts of Holger Blum and Erik Glemme, chief designer from 1936-1956. (Worpole 95)

The first abstract play sculptures and its way to the US

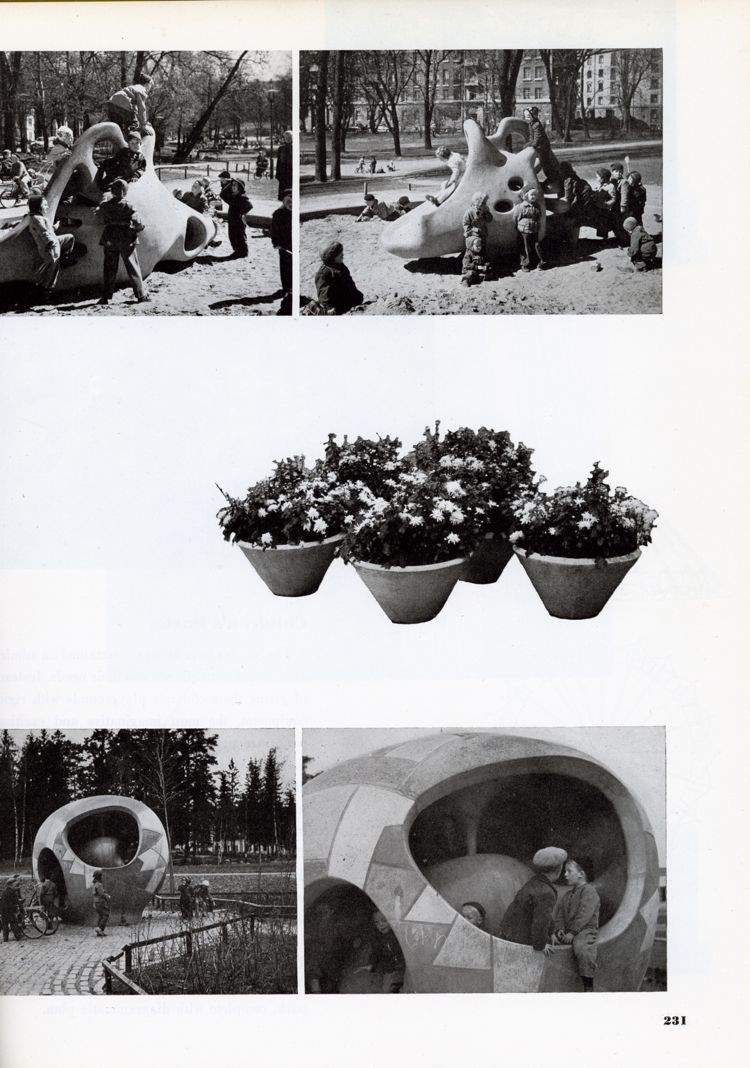

In 1949, the Parks Department installed Tufsen by Danish sculptor Egon Møller-Nielsen in the city park Humlegården. It is an organic, abstract shape placed in a pool of sand, a contrast to the conventional shapes of that time, mostly animals.

George Everard Kidder Smith (1913-1997), an American architectural writer and photographer traveled to Scandinavia, as holder of the 1939-1940 followship, given by the American Scandinavian Foundation, to do research in Modern Swedish architecture. His reportage was presented in a traveling exhibition by MoMA (1941) and in a book „Sweden builds“ (1950).

Progressive Architecture affirmed that „The significance of Sweden as a source of modern achitectural design is safely attested“ and „that Swedish architects have set a high standard in town and community planning, in the application of the expanding cooperative movement“ (Progressive Architecture, Aug. 1941).

In 1953, Frank Caplan, the founder of the American toy company Creative Playthings, traveled to Sweden as well. There, he met with Møller-Nielsen and once back in the US, Caplan started to commercialize Møller-Nielsen’s play sculpture Spiral Slide. This marked a shift, since for the first time, recreation officials in the US could order something different than the usual steel pipe swings, monkey bars and see saws.

©Gabriela Burkhalter

sources:

Treib, Marc. The Architecture of Landscape, 1940-1960. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

Worpole, Ken. Here Comes the Sun: Architecture and Public Space in Twentieth-Century European Culture. London: Reaktion, 2000.

Burkhalter, Gabriela: When Play Got Serious, in: Tate etc. Issue 31-Summer 2014, London www.tate.org.uk/tateetc

image Tufsen: Swedish Museum of Architecture Collections, Stockholm

Crisis in the Polpulation Question, wikipedia

posted: Mai 24, 2014. Ergänzt: 8. Dezember 2015